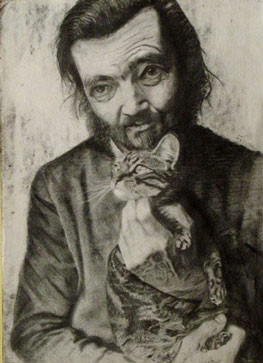

X-Ray of Julio Cortázar

by Víctor Montoya

(Image: Paula A. Fassina's drawing on a photograph of Ulla Montan)

I harbor the hope that someone will share with me the extraordinary impression that this photograph produced when I saw it. Some admirer –male or female– had cut it out of a magazine and carefully taped the four corners on a hospital window. Examining it closely, I became engrossed in the illumination on the forehead that gives it such a vivid focus. I couldn't resist the temptation to take it, so that I could describe it for those who weren’t acquainted with it. But I came to recognize that it wasn't an easy task, but a constant struggle against my subjectivity that kept watching me in my futile attempt hour after hour to write a description. Only those who have spent hours awake with a persistent idea will understand the desperation caused by trying to find the exact words to describe a photograph that in itself is poetry composed of light and shadow.

Dear Julio, in this photograph, more than in any other, you look at us from the depth of your tender eyes. While your face, marked by a profound expression of melancholy, inspires deep respect and admiration for what you were in circumstances of simplicity and silence, in which you learned to communicate more by your expressions than with words. Like every great writer who manifests his thoughts and feelings through the written word, with those small graphemes you, since you were a child, wrote with your finger in the air, as if it were a matter of magic signs born of your imagination or coming from a palindrome, in which the word Roma became amoR when inverted.

Looking intensely at this photograph of you with your pony tail and lion-like beard, grown as rebelliously as the flames in your soul, I imagine you at your desk, a kind of giant lost in Wonderland, listening to jazz improvisations, reading your favorite books, or simply stroking the back of your cat, Flanelle, whose purring was the only music breaking the monotony of the silence.

A quick glance at your long-sleeved, high-necked pullover and I imagine you in winter, sloshing through the damp streets of a gray city, wrapped in a big scarf, and in the summer, stretched out under a tree, your eyes fixed on emptiness and meditating on the dimension of your work, in which fantasy and reality fuse into the two sides of the same medal. Sometimes, I seem to hear you talking in your Argentine accent with the French influence on the "r," about Fidel and the Cuban revolution, a country where you rediscovered happiness, solidarity, spontaneity and Latin American themes, after having spent half of your life in Paris, in that city that you loved and hated at the same time.

When I read one of your letters written to Fernández Retamar –Director of Casa de las Américas (our house)– I was breathless, my heart broken, unable to explain how a “cornucopia” of your stature could feel alone and foreign in District 15, a recluse in a tall, narrow, little house, like your portrait. More recently, however, rereading El perseguidor (The Fugitive), the excellent short story inspired by Charlie Parker, the famous Bird, the jazzman, who hallucinated with drugs and alcohol, and who, with his saxophone, made lovers of his music hallucinate, I can understand the reason for your loneliness, and your overwhelming love for humanity and their affairs; because the life of Charlie Parker taught you to look inside to the depths of your being, beyond the superficiality that eats away at us every day. For the same reason, I must tell you that your sensitivity –or hypersensitivity– as a man of letters, led you to take up the cause of social justice and the defense of sociopolitical causes of the people; the proof is in the position you assumed regarding the Cuban Revolution with the events in May, 1968 in Paris, and with the Sandinista Revolution you portrayed so well in Nicaragua tan violentamente dulce (Nicaragua So Violently Sweet). Undoubtedly your literary work was rooted in the struggles for emancipation; from these you understood that democratic socialism was the only historical alternative capable of abolishing the exploitation of man by man. But now that you aren’t with us, death having prevented your seeing the changing directions in the world from the fall of the Berlin wall to the tragic resurgence of nationalisms, I can only imagine that you would not take one step back, convinced that humanity won’t turn the wheel of history and will resist buffeting imperialism the way that Cuba is, that small island and that great cause that you loved so much during your life.

So, then, dear Julio, before your beautiful portrait that pictures the soul of a big old good kid, I declare once again that you were a true “cornucopia,” a magnificent human being, whose spirit was a vessel for the best of human values, a man in whom you could place the utmost confidence as if into a little box holding the most intimate secrets locked under seven keys; moreover, seeing your big, freckled hands, I can verify that your boxer arms are ready to go against the adversaries of the dispossessed in El último round (The Last Round), and in it we, the advocates of your works, which are as great as your life, will go with you.

📨

Contact with V. Montoya:

montoya [at] tyreso.mail.telia.com

Más artículos de Víctor Montoya

▫ Artículo publicado en Revista Almiar (2002). Reeditado en agosto de 2019.